This is a continued post from 11 Basic Study Methods.

This is a reminder that applying methods without understanding the principles wastes time and energy. Once we understand the principles, we can mix and match the strategies to develop our personalized study system.

“Hard work is not always something you can see. It is not always physical effort. In fact, the most powerful form of hard work is thinking clearly. Designing a winning strategy may not look very active, but make no mistake: it is very hard work. Strategy often beats sweat.”

James Clear

1. Scope the Subject

When we learn something new, it's critical to understand how it fits with what we already know. This is where "Scoping the Subject" comes in. Scoping the subject is most effective at the beginning of a study session or when learning something new. It involves asking ourselves how much we already know about a subject before diving in. Essentially, scoping the subject is taking the time to go through our entire subject and conduct an extensive audit of all the topics we have to cover.

Methods of Scoping the Subject

There are several ways to scope a subject:

Mind Mapping: Creating a mind map helps visualize what we know and how it connects.

For example, you're about to study cell biology. Before starting, you create a mind map with "Cell Biology" at the center. You branch out into categories like "Cell Structure," "Cell Function," "Cell Division," and "Cellular Respiration." Under each category, you list what you already know and identify gaps in your knowledge. This visualization helps you understand how different concepts are related and what areas to focus on.

Skimming the Textbook: Go over the chapter quickly, noting recurring words, phrases, or unfamiliar topics. Skimming will help us identify gaps in knowledge and turn them into learning targets. This approach gives our minds a focus. Knowing what to pay attention to without a precise aim is hard.

For example, you're starting a new chapter on the American Civil War. You skim through the chapter, noting critical terms like "Gettysburg," "Emancipation Proclamation," and "Confederacy" that you are unfamiliar with. You highlight these terms and make a list of them. This list becomes your study guide, giving you specific topics to focus on.

Reviewing a Syllabus or Exam: Similarly to skimming a textbook, we can review a class syllabus or study guide to see which topics will be covered. We can find what we know and don’t know so we know what to look out for when we cover the material.

For example, at the beginning of the semester, you review the syllabus for your calculus class. You make a list of the topics covered, such as "Limits," "Derivatives," "Integrals," and "Sequences and Series." For each topic, you jot down what you remember from previous math classes and what seems completely new. This helps you prepare mentally for the areas that will require more attention.

Researching for a Paper: Before we write something, we can list themes we will touch on in the paper. We can write what we understand and what we don’t to get a better idea of what needs to be researched.

For example, you're writing a paper on the Industrial Revolution. Before diving into research, you scope the subject by listing out key themes like "Technological Innovations," "Economic Impact," "Social Changes," and "Key Figures." You then outline what you already know about each theme and what you need more information on. This structured approach guides your research process.

Benefits of Scoping the Subject

One significant advantage of scoping the subject is creating a ready-made list of concepts to learn. This list can be prioritized, which is crucial for effective scheduling and timetabling.

Another significant advantage is we can quickly identify relevant information and focus our energy on comprehension rather than apprehension.

2. Build Knowledge Frames

Knowledge frames are a powerful way to learn and understand complex concepts by breaking them down into simpler, more manageable parts. They work particularly well with mind maps, which can be seen as a type of knowledge frame.

The idea is to build a basic understanding of a concept and then expand on it by adding details over time.

Dr. Andre Pinesett, a Stanford-trained medical doctor and expert in student success, advocates for this method. He emphasizes that students should start with a simple concept representation and gradually add details. For example, learning the flow of blood through the heart can be made much simpler using knowledge frames.

Creating a Simple Knowledge Frame

Let's take the flow of blood through the heart, a concept many people find challenging to memorize.

One could memorize the flow of blood through the heart:

Vena cava → right atrium → tricuspid valve → right ventricle → pulmonic valve → pulmonary artery → lungs → pulmonary veins → left atrium → bicuspid valve → left ventricle → aorta → the rest of the body…

… But that’s not intuitive, especially if we aren’t familiar with anatomy.

Instead of memorizing the flow through brute force, we can use a knowledge frame to make it intuitive.

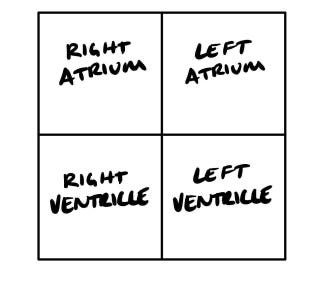

First, we have to create a simple and generalized conceptualization of blood flow through the heart:

This is the heart, or at least an extremely simplified version. This box will be our initial knowledge frame. As long as we think about the heart like this, it will be easier to learn the smaller details. Now that we’ve built the foundational structure, let’s hang some details on it.

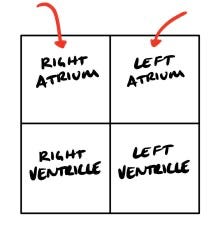

The first detail will be the entry of blood into the heart. Blood only comes into the heart through the atriums from the top, starting at the right atrium.

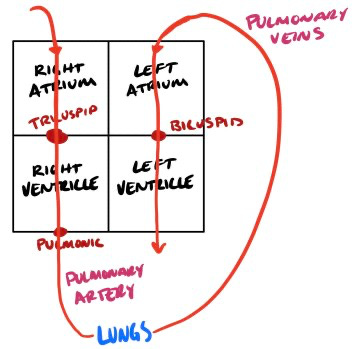

The next detail is to add the valves. Three valves—tricuspid, bicuspid, and pulmonic—are between each opening so the blood doesn’t flow backward.

Sometimes, we must combine other memory tricks to get the details right.

The tricuspid and bicuspid valves are between the atrium and ventricles, and the pulmonic valve is between the right ventricle and the lungs. I remember this through the classic mnemonic “Try it before you buy it.” The pulmonic valve is named such because it leads to the lungs, and things related to the lungs are known as pulmonary.

Veins carry blood towards the heart, and arteries carry blood away from the heart. Thus, blood leaves the right ventricle through the pulmonary artery and enters the heart through the pulmonary veins.

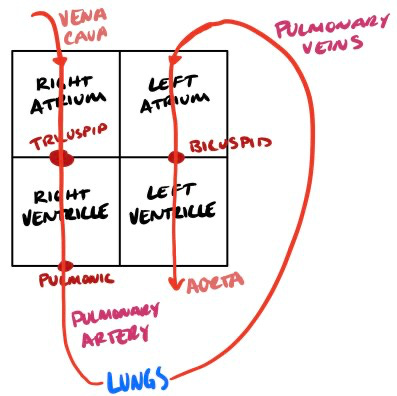

The next detail is to name the heart's entries and exits. Blood enters through the superior and inferior vena cava and exits through the aorta.

And there you have it! How to memorize the entire flow of the heart in four steps.

We can always memorize complex systems and ideas, but there may be a less burdensome way to understand them.

Now that we’ve created a knowledge frame, we can even draw it out as a form of active recall.

I’ve also used this idea (before I knew it had a name) in my chemistry classes to learn VSEPR theory intuitively and to understand cellular respiration and all its little details.

It’s difficult and time-consuming to create knowledge frames, but once they are made, they are invaluable. Our understanding becomes solidified, and our retention skyrockets.

Find ways to simply concepts, then hang the smaller details on your frame.

3. Articulate Failure and Success

"When things cannot be defined, they are outside the sphere of wisdom, for wisdom knows the proper limits of things."

Seneca (Letters from a Stoic XCIV – On the Value of Advice)

Clearly defining failure and success is essential for effective learning and achieving goals. As purpose-driven creatures, we thrive with clear objectives to strive towards. Not only do we experience dopamine releases as we move towards our goals, but having specific targets also helps us stay on track.

Setting Intentions and Boundaries

Setting clear intentions and boundaries for failure and success is crucial when studying.

This means having concrete goals to measure your progress, not just relying on time spent studying.

Here are some examples of how to articulate success and failure in different situations:

Regarding practice questions:

Goal: Complete practice questions covering specific topics until you can do them without mistakes.

Failure: Struggling to complete the problems or making frequent mistakes.

Success: Consistently solving problems correctly without errors.

Regarding completing chapters:

Goal: Finish studying one chapter of new information per day.

Failure: Not completing the chapter within the day.

Success: Complete the chapter and understand the content thoroughly.

On quantitative goals:

Goal: Complete a set number of practice problems, such as 20 problems, in a study session.

Failure: Completing fewer than 20 problems or getting many wrong.

Success: Finishing all 20 problems and understanding the solutions.

Real-Life Application

When working with my students, I set goals like completing practice questions without mistakes. This provides a precise measure of progress and success.

When my wife was studying for the MCAT, she aimed to finish one chapter of new information daily. This way, she knows precisely when she’s done studying for the day, avoiding the aimlessness of "studying as much as we can."

Beyond Studying

This lesson can be applied to various areas of life. Articulating goals is a higher level of understanding and can significantly impact our lives. By setting specific, measurable objectives, we can better track our progress and achieve our ambitions.

Setting clear boundaries for failure and success will help us stay focused, motivated, and on track to reach our goals.

4. Breakdown Past Papers, Exams, and Essay Plans

I mean this with all my heart. Textbooks, the internet, fantastic tutors, and friends are all great resources, but nothing compares to old exams and thorough essay plans.

The Value of Old Exams

When we study for an exam, we aim to answer the questions on that test. The best way to achieve this is by practicing with the same types of questions that will appear on the exam. However, when creating active recall questions, many students, myself included, often wonder if the questions they use are sufficient.

I've heard and thought countless times, "I didn't study any of the stuff that was actually on the test." There's nothing worse than preparing for the wrong material, especially when the stakes are high. Studying the wrong material is incredibly frustrating. We put in the work, only to find out we've sacrificed the wrong things.

Nothing beats studying old exams or past papers, especially if they were administered by the same professor. This way, we know what their tests are like. We know the types of questions to expect, the wording, the exam length, and many other details. Reviewing an old test removes much of its uncertainty, boosting our confidence and reducing anxiety. Anxiety is our response to preparing for unknown variables and studying past exams eliminates many unknowns.

If old exams aren’t accessible, practice tests covering the essential concepts for most STEM classes are usually available at the end of textbook chapters.

The Power of Essay Plans

If you need to write an essay, examining the structures and characteristics of past essays can provide a stronger framework, especially under timed constraints. When reviewing an old essay, ask yourself:

How did they structure this paper?

Why did they structure it that way?

What are the weaknesses of this paper? Avoid those.

What are the strengths of this paper? Mimic those.

Plagiarism is unethical, but finding inspiration from others is entirely fair. In Austin Kleon’s Steal Like an Artist, he discusses the uniqueness of each individual and how it affects our ability to imitate. Kleon suggests that trying to copy another’s work will inevitably result in a new creation influenced by individualism. I believe this is true. By allowing ourselves to be influenced by our surroundings, we naturally influence the world around us. When looking over old papers, mimic as much as possible. Steal the concepts, plans, and ideas, but let your voice shine through and make them your own.

Practice, Practice, Practice

Once you’ve gathered the ideas for your essay, write out an outline repeatedly until you can write that essay in your sleep. The repetition solidifies your understanding and prepares you for success.

Focusing on past papers, exams, and thorough essay plans can ensure we study the right material and confidently approach our exams and essays.

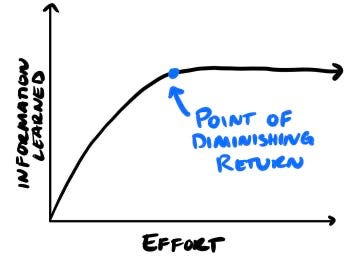

5. Work Until the Point of Diminishing Returns

“The last 10 percent of performance generates one-third of the cost and two-thirds of the problems.”

Norman R. Augustine

The concept of diminishing returns is widely recognized and can be found in various aspects of life. Understanding these principles can significantly impact how we approach different situations, especially studying.

The Point of Diminishing Returns occurs when the ratio of output to input decreases to a level where it's no longer reasonable to continue. In the context of studying, this is when you have to exert more effort to learn less. Eventually, this point can lead to Negative Returns, which should be avoided at all costs.

The 85% Solution

Ramit Sethi advocates for “getting the big wins” and then moving on based on stopping at the point of diminishing returns. He calls this the 85% Solution—get 85% of it right and then move on! Ramit believes that 50% of our effort will get us to 85% completion. The last 15% requires the other 50% of our effort.

While this heuristic may not always accurately predict the point of diminishing returns, I think it can serve as a good rule of thumb.

Diminishing Returns of Studying

When I teach, I sometimes tell students, "Don’t worry about this, and plan to get it wrong on the test," if a problem takes too long to solve. This shocks some people but frees up time to cover more material.

Instead of aiming for 85%, I suggest the 90% Solution – get 90% of it right and then move on.

Be advised - sometimes, we must put in that extra effort to get that last 10% right.

Finding Your Point of Diminishing Returns

The point of diminishing returns varies for each individual and each situation. Several factors can determine this, but the most significant is our trajectory—our plans.

Clearly articulating our goals helps determine if our efforts are worthwhile.

Knowing where we are going allows us to understand our present circumstances better and decide whether to push harder or back off.

We don’t have the energy to fight every battle. We must pick and choose. We must know when to back away and when to push forward.

Effort doesn’t always equal better results. By being mindful of this principle, we can study more efficiently and use our time and energy more wisely. Focus on what's most important, achieve a solid understanding, and then move on to the next challenge.

6. Avoid Multitasking

Human beings are incapable of multitasking; what we do is better thought of as task-switching or context-switching.

According to the American Psychological Association (APA), we never genuinely do more than one thing at once. We may switch contexts so quickly that it appears we are multitasking, but that is just an illusion.

For example, if I were writing this paragraph at the same time I was producing a song, I would struggle because my brain would constantly switch between the two tasks. When focusing on the paragraph, my brain creates new connections between ideas and figures out how to lay out thoughts in a linear language. However, when I switch to music production, my brain focuses on sound selection, volume levels, and the flow of the music. These two tasks require different cognitive processes, and constantly switching between them prevents any deep work from happening.

The Importance of Deep Work

Deep work refers to focusing without distraction on a cognitively demanding task. Not engaging in deep work keeps projects at a mediocre level. The highest quality products, ideas, books, songs, and other works are created during long stretches of uninterrupted time.

Let's say I spend three hours switching between blogging and producing music. Ideally, I would end up with a fantastic blog post and mix. However, if I switch tasks every 15 minutes, I only work on the blog post or the music for short bursts, which isn't enough time to produce high-quality work. In my experience, nothing amazing is created in 15-minute intervals for either of these art forms.

A Note On Focus

To produce quality work or study efficiently, we must focus on one task for an extended period. Working on multiple responsibilities for six hours straight is a losing strategy. We would be much better off spending an hour or two on just one task rather than straining our brains trying to do everything simultaneously.

Additionally, keeping distractions at a minimum is crucial to maintaining focus. Context switching is easier than we’d like to believe. Even one tiny notification can rip us out of flow, so I recommend working with notifications off.

Listening to certain music while working can also take us out of flow. When we listen to music, our brain has more input to process, adding extraneous cognitive load to our plate. While I enjoy working with music and find the slight productivity hit worth it for the enjoyment, I avoid music with lyrics.

Lyrics can pull us out of flow faster than instrumental music because our brains will want to process the words and extract their message, resulting in a context switch and serious hits to productivity.

Focus on one thing at a time. Work with notifications off. It takes 25-30 minutes of uninterrupted time to get into flow. We are all incapable of multitasking, and resisting that idea results in harder-to-complete, lower-quality work. Attempting to multitask is rarely worth it, especially when creating or working on something we care about.

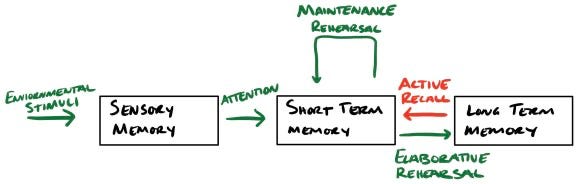

7. Use Maintainance Rehearsal & Elaborative Rehearsal

Have you ever had to memorize a phone number? Whenever I have to, I say it to myself a few times, and once I dial the number, I instantly forget it! This type of thing happens whenever I know I have to memorize something quickly that I know I don’t need later down the line.

I used to do this with vital signs when I was with patients. I’d take their vitals, say them to myself repeatedly, write them down, and then forget them. I might remember the general idea but not the exact numbers. It may be a bad habit, but I’m human, and my brain is trying to survive. This little trick is known as Maintenance Rehearsal.

Maintenance Rehearsal

Maintenance rehearsal keeps information in our short-term, or working, memory, which depends on our cognitive load. It’s fantastic for memorizing information quickly but requires relatively little attention and doesn’t need to be deeply thought about.

However, I do not recommend using maintenance rehearsal for studying. While it’s a neat trick our minds can do, it's unsuitable for transferring information to long-term memory.

Elaborative Rehearsal

Elaborative rehearsal is much more suitable for studying. This is more effective for transferring information from our working memory to our long-term memory (LTM), which is the goal of most learning. It involves thinking and internalizing the meaning of the information, which is an attention-expensive process.

Elaborative rehearsal is effective because it requires depth, similar to why active recall works so well. Using our brain to think about the meanings, accommodating new information, and connecting it to what we already know is an incredibly effective tool for moving information into our LTM. We do this when we think about a good novel or learn something that reminds us of something in our personal lives.

Practical Applications

Maintenance Rehearsal:

This is great for phone numbers, passwords, or other small tidbits that don’t need to be moved to our LTM.

Useful for temporary information retention.

Elaborative Rehearsal:

It is ideal for studying and long-term learning.

Find meaning in things, connect them to our lives, and learn deeply.

While maintenance rehearsal is fantastic for quick memorization, elaborative rehearsal is what we should focus on as students. When we find the meaning in things and connect them to our lives, we learn deeply. This will ensure that the information we study moves from our short-term to our long-term memory, making it available whenever we need it.

8. Account for Spill Days

Why Spill Days Matter

Scheduling is crucial for productivity, but let's be real—life doesn't always go as planned. Back when I was a tutor in college, I used to line my students up back-to-back to maximize the number of sessions in a day. However, if one session ran late, it threw off the entire schedule. This was not sustainable.

The same issue arises with planning busy days. We plan the perfect day, and then something unexpected happens. Do I push everything off until tomorrow? That’s not feasible because tomorrow has its tasks.

Enter Spill Days

Spill Days are specifically designed for catching up on all the things that don’t get done when life happens. I usually schedule them after a busy day with family or friends since I typically have those days to myself.

They can be as frequent or infrequent as you need.

How to Use Spill Days

Unexpected Events: Something unexpected came up? Assign the displaced tasks to a Spill Day.

Tasks Taking Longer Than Expected: If a task takes way longer than planned, move the non-time-sensitive tasks to a Spill Day.

Time-Sensitive Tasks

Spill Days are not helpful for tasks that need to be done immediately. In these cases, I would reschedule non-time-sensitive tasks to a Spill Day and focus on the urgent task.

Real-Life Example

Once, I saw a job posting that I wanted. Applying was time-sensitive, but I planned to do other creative work that day. Since I had more time to do my creative than apply for the job, I rescheduled the creative day to the nearest Spill Day (before the due date) and focused on the application. By the end of the week, I had an interview and produced a song. Even though I didn’t get the job, I fulfilled my responsibilities and maintained my productivity.

Spill Days are crucial. Our lives rarely go as planned, and we all need time to catch up. Knowing you have a Spill Day coming up reduces stress when things don’t go as planned because you know your responsibilities will still be accomplished.

9. Schedule Around Our Body’s Natural Rhythms

We all have a natural rhythm, much like the steady beat of a heart, known as a normal sinus rhythm. It's a sign that everything is working the way it should. This rhythm is not just limited to our hearts; our entire bodies follow various rhythms that dictate our daily functions.

Understanding Our Rhythms

Humans are rhythmic creatures. Our bodies operate through a cascade of reactions, each doing its own thing but working together to create something spectacular: the human body.

This inherent rhythm is part of nature and governs our sleep, eating habits, and more. Even animals, like my dogs, have their rhythms, knowing when it's time to eat, walk, or sleep.

The key is understanding and working with our personal rhythms to maximize productivity and minimize resistance.

Have you ever tried working on a paper when you're sleepy? It’s challenging enough to do the work, but staying awake adds another layer of difficulty. This double effort makes us less likely to repeat the action, making future tasks even harder.

Types of Rhythms

There are four main types of rhythms in the body:

Circadian Rhythms: These are 24-hour cycles that include physiological and behavioral rhythms like sleeping. I aim to schedule my most important work between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m., when I’m most alert. Less demanding tasks are saved for the evening when I have less energy.

Diurnal Rhythms: These are circadian rhythms synced with day and night. I try to align my schedule with my natural sleep/wake cycle. Although I sometimes have to get up early for specific tasks, I generally rise around 8 am and go to bed by 11 pm or midnight. This helps me work with my natural rhythms instead of forcing productivity.

Ultradian Rhythms: These are shorter periods with higher frequency than circadian rhythms, like eating cycles. I pay attention to when I get hungry and plan my meals to avoid interruptions during peak productivity hours. For example, I have a light, high-protein breakfast to avoid crashing during my peak hours from 10 am to 2 pm and avoid late-night eating to stay alert in the mornings.

Infradian Rhythms: These last more than 24 hours, such as the menstrual cycle. For women, it's beneficial to consider the menstrual cycle when planning physically demanding tasks to avoid unnecessary stress. While men may not experience this, everyone can practice scheduling around their longer-term cycles.

Practical Application

While not everyone can control their schedule perfectly, planning daily activities with these rhythms in mind helps significantly reduce stress.

By working with our natural rhythms, we reduce resistance and the need for willpower, making it easier to complete tasks efficiently. While it may not always be possible to align every activity perfectly, being mindful of our rhythms can help us manage our time and energy better, leading to a more productive and less stressful life.

10. Create a Guiding Environment to Minimize Willpower

"Your environment will eat your goals and plans for breakfast."

Steve Pavlina

Whenever I start something, I often find myself looking for ways out. When I encounter any friction, I usually decide it’s not worth the energy and stop. This was a huge problem for me when I was younger. Initially, I thought I had to ignore the friction and brute force my way through it. But I couldn’t do that consistently, and it was extremely difficult. I needed a method that made things easier and worked every time I tried it. Then it hit me!

Lessons from Reverse All-Nighters

I realized I needed a place where my work would be easy, free from distractions and friction. As a high school senior aiming to become a doctor, I knew I needed to get serious about my work. I identified distractions as my main problem and decided I needed a distraction-free zone. My solution was somewhat radical: reverse all-nighters. I would sleep as soon as I got home from school at 3:00 pm, wake up after 8 hours at 11 pm, and then work all night into the next school day.

This experiment taught me a lot. Though it was terrible for my retention and made me mentally useless the next day at school, I could focus on my work like never before. The late-night atmosphere was perfect for productivity because there were no distractions. It was brutal, but my environment kept me on the path.

Fine-Tuning the Method

Today, I’ve refined this method to create guiding environments that aren’t detrimental to my health. My home office is now set up so I can do all my work with as little friction as possible. Creating spaces conducive to the functions we use them for is key.

Tips for Creating a Guiding Environment

Identify Distractions: Pay attention to what pulls you away from your work and find ways to eliminate or reduce these distractions.

Designate Work Zones: Create specific areas for different types of work. For example, have a separate space for studying, working, and relaxing.

Optimize for Functionality: Ensure your workspace is set up to minimize friction. This could mean having all necessary tools and materials within reach, ensuring comfortable seating, and abundant lighting.

Schedule Wisely: Align your work periods with your most productive times.

Use Technology Wisely: Utilize apps and tools that enhance productivity but limit access to distractions like social media during work hours.

Maintain Your Space: Keep your work area clean and organized to foster a productive mindset and clear thinking.

Creating a guiding environment reduces the need for willpower by making it easier to stay on task. Minimizing distractions and optimizing our workspaces can enhance productivity and make our goals more achievable. While everyone’s optimal environment will look different, the key is to design spaces that support and guide us toward our objectives with minimal resistance.

11. Use Mnemonic Devices to Remember

Mnemonic devices are powerful tools that aid in memory retention and recall. These techniques can transform difficult-to-remember information into easily accessible knowledge. They are especially useful in educational settings, helping students remember complex concepts and details.

What Are Mnemonic Devices?

Mnemonic devices are strategies that improve memory by associating new information with something familiar and easier to recall. They often involve vivid imagery, patterns, or associations that make the information more memorable.

Types of Mnemonic Devices

There are several types of mnemonic devices, each serving a unique purpose:

Acronyms and Acrostics

Acronyms create a word from the first letters of a series of words. For example, NASA stands for National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Acrostics form a sentence where each word starts with the first letter of each piece of information you want to remember. For example, "Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge" helps music students remember the notes on the lines of the treble clef (E, G, B, D, F).

Rhymes and Alliteration

Rhymes create a catchy, memorable pattern, like "In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue."

Alliteration repeats the same initial consonant sounds in words, like "Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers."

Chunking

Chunking breaks down large amounts of information into smaller, more manageable units. For example, we might remember a phone number as 123-456-7890 instead of 1234567890.

Imagery and Visualization

Creating vivid mental images related to the information helps improve recall. For instance, to remember a grocery list, you might visualize a giant carrot dancing with a loaf of bread.

Method of Loci

Also known as the memory palace technique, this method involves associating items to be remembered with specific physical locations in a familiar place. For example, imagine placing items around your house as you walk through it in your mind.

Peg Systems

This technique involves associating numbers with words that rhyme or sound similar, creating an easy-to-remember list. For example, one is a bun, two is a shoe, three is a tree, etc.

Benefits of Mnemonic Devices

Enhanced Memory: Mnemonics improve the ability to remember information by making it more meaningful and easier to recall.

Increased Learning Speed: Mnemonic devices allow for faster learning and comprehension by simplifying complex information.

Reduced Cognitive Load: These techniques help reduce the mental effort required to remember information, freeing up cognitive resources for other tasks.

Engagement and Enjoyment: Mnemonics can make learning more engaging and enjoyable, encouraging a positive attitude toward studying.

How to Create Effective Mnemonics

Use Vivid and Unusual Imagery: The more vivid and unusual the imagery, the more likely it is to be remembered.

Make It Personal: Relate the mnemonic to something personal or familiar to make it more meaningful.

Keep It Simple: Ensure the mnemonic is simple and easy to remember. Overly complex mnemonics can defeat their purpose.

Practice Regularly: Regular practice and repetition of the mnemonic will reinforce the memory association.

Popular Examples of Mnemonics in Education

To remember the order of operations, students use "PEMDAS" (Parentheses, Exponents, Multiplication and Division, Addition and Subtraction) or the phrase.

The acronym "HOMES” (Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, Superior) is used to remember the Great Lakes.

For the classification of living organisms: "King Philip Came Over For Good Soup" (Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species).

These strategies help us study smarter, not harder, ensuring our efforts produce meaningful and lasting results.